A talk given by

Professor Barbara English

at The Friends of Beverley Minster Annual General Meeting on 19 April, 2021.

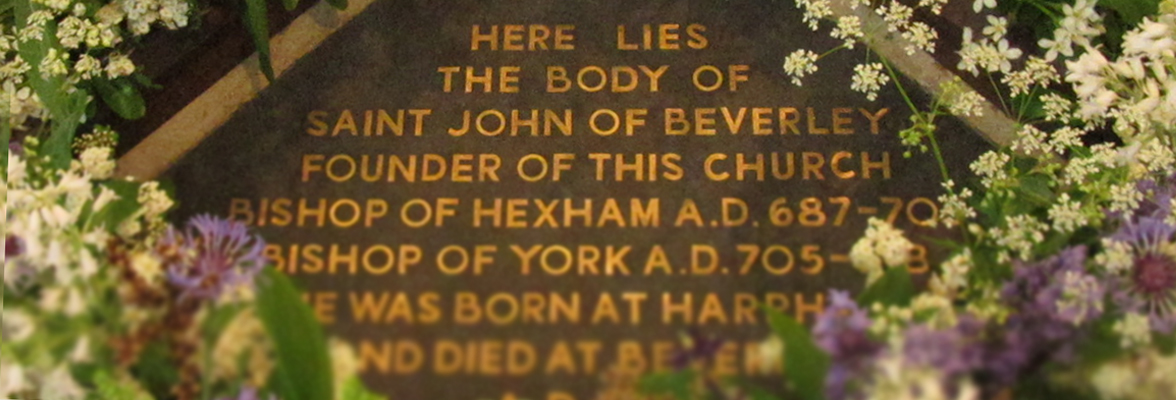

Let us start with a quotation from the 20th century floor slab in the nave of Beverley Minster

“Here lies the body of Saint John of Beverley”

My question is ….does it really?

In 2021 it is 1300 years since John’s death,

and 600 years since the visit of King Henry V to Beverley,

to give thanks to St John for his help at the battle of Agincourt in 1415

(yes it did take Henry a long time to get here, but after Agincourt he was hardly ever in England, trying to hold on to France meant perpetual war).

St John died on 7 May 721, and Henry visited on 8/9 April 1421. But the date that ties the two anniversaries together, is actually 25 October, the day on which Agincourt was fought, and the day of the year on which the container of St John’s remains were ‘translated’ for the last time to lie inside the new and glorious casket, made by the London goldsmith Richard of Faringdon. In Shakespeare’s play, King Henry on the eve of battle, says ‘This day is called the feast of Crispian.’ I always regret that Shakespeare did not say, ‘This day is called the feast of the Translation of St John of Beverley’ but you do see it is hard to get all that into the majestic roll of the pentameters of that amazing speech – and even after omitting St John, Shakespeare had to play around with two names, Crispin and Crispinian, saints, martyrs, shoemakers and apparently twins, who died on 25 October, centuries before John was translated.

Translation is the moving of the body of a saintly person out of the ground and into a special place. In Catholic Europe, if miracles began to occur at a grave, people thought it was inappropriate to leave the saint’s body in the ground along with everyone else, and saints were usually, nearly always, dug up and moved upwards and usually eastwards. There were then two holy places, the empty tomb, and the shrine (there are various Latin words for these places, I am going to use tomb and shrine). John was originally buried at the east end of the Minster, east of the high altar. He was recognised as a saint locally, and his sanctity was confirmed by the archbishop in 1037 (by the 12th century only the pope could do this). Leland in the early 16th century recorded in his Collectanea, that the saint’s bones were translated, that is, moved, 316 years after his death, and another source (Dugdale, Visitation 1665) suggests he was moved to the high altar. In the grave says Leland (Beverley Chapter Act Book II p.350), at the Translation of 1037 they found a ring and a fragment of the Gospels; Dugdale mentions beads and nails. It was probably in 1037 that the first reliquary was made for John, separate from his tomb.

The reliquary of St Taurin, made in Paris c.1240

Reliquaries are a fairly standard shape, little houses with pitched roofs – they became more and more decorated, looking more like little churches, and may have been designed by architects and constructed by goldsmiths. The goldsmith’s contract for John’s last shrine of 1292 specified it was to be ‘adorned with plates and columns in architectural style with figures everywhere of size and number as the Chapter determine, and canopies and pinnacles before and behind, and other proper ornaments.’

We have the dimensions of the outer casing, it was to be 5 ft long, 1.5ft wide and of proportionate height: the inner chest must of course have been smaller and was not large enough for a skeleton, but would hold bones and maybe some other relics, a seal, a ring, clothes, holy books. All this gold, silver and jewels was taken in 1548 by the Protestant government of Edward VI, and there is no record of what happened to the contents. Are we to accept that the relics went back under the nave floor?

It is important to realise that for many saints, the Translation was regarded as equally or more significant than the date of death. It marked the full achievement of recognised sainthood. Translations were the occasions of great church festivals which could last for days, and the offerings of the people on the annual Translation feast of, for instance, Thomas Becket, were much greater than on the day of his death. Major saints could be translated many times. This was partly for religious reasons, to honour the saint with a better place, but also because the church was constantly being rebuilt, extended, altered. Cuthbert of Durham, whose post mortem wanderings were legendary, was translated 4 times, as was Swithin of Winchester; William of York 3 times. At translations it was common practice to remove pieces of the saint to give to ‘important people’ – some archbishops expected an arm for presiding over a translation, and sometimes, says Ben Nilson in a great book on shrines, the cost could be ‘an arm and a leg’.

There are descriptions of an exhumation for a translation, and it was an elaborate religious ceremony – the tomb was opened at dead of night, the remains carefully washed, wrapped and placed in a new chest. John’s bones, first separated from his grave in 1037, were translated again in the 1060s, possibly after the fire of 1188. Horrox thinks the bones were put back into the grave after the tower fell around 1213, but probably moved out again in the mid 13th century. John was translated yet again in 1307 on 25 October, when the relic chest (the feretrum) was put into the very elaborate gold, silver, enamel, jewelled casket made by Roger of Faringdon, an outer casing (the capsula) that could be raised on pulleys to reveal the interior chest. It is the date of this 1307 move that became the established feast day, the Translation of St John of Beverley. The inner chest or perhaps both inner and outer golden boxes were carried around Beverley for 4-5 days in the summer before the annual Cross Fair, and 25 October, the date of the 1307 move, that is the one that chimes with Agincourt.

You will remember that St Swithin at Winchester disapproved of being moved, as he made it rain until he got his own way. St John’s relics on the other hand was processed around the outside of the Minster around 1100 to break a long Yorkshire drought, and while crossing the east end, the heavens opened and the clergy got very wet. It was a miracle.

So – can we still say with confidence

“Here lies the body of Saint John of Beverley”

A red herring for you to think about – a 19th century anonymous writer (Sketches of Beverley and the Neighbourhood) says the stairs in the north choir aisle to the two storey chapter house were for the Shrine of St John. Is there any chance that this is right? There is one miracle story that says the tomb cover had polished marble shafts, and of course the stairs do have polished ‘marble’ shafts, but then so do many other parts of the Minster. Two-storey chapter houses are rare in England (only 7, although they include Westminster, Wells and Rievaulx). To my surprise, Lichfield claims its own ‘Chapter House is the only two-storey Chapter House in the UK,’ in a press release for a restoration grant which they got – a careless application, with an error easily detected.

As an old historian myself, the Minster stairs would be a challenge as they are at Wells. Would the canons of Beverley who also had old knees, want to climb up daily and perhaps more than once a day? To have a sacristy and treasury underneath? Should we revisit this interpretation of those wonderful stairs?

Finally

On 25 October we will at Beverley celebrate the Translation of St John, and Henry V’s visit because of that Translation. We will not forget it, nor I hope will those that come after us.

I’d like to end with 4 lines from that famous speech:

And Crispin Crispian shall ne’er go by

From this day to the ending of the world,

But we in it shall be remembered;

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;

Not that the Friends are few – for they are many. But remember we should.